Q: How did you start your career as a historical flutist, and what led you to specialize in the Baroque flute?

When I was little, I remember that my father had cassettes of “The English Consort,” who were pioneers in historical instrument interpretation. There were two, one with Handel’s “Water Music” and another with Bach’s “Brandenburg Concertos.” I always listened to them; the sound was quite exotic, and that flute I heard was nothing like my metal flute, which I was learning with my private teacher. Later, when I was at the conservatory, I realized there were people specialized in performing music from other periods with original instruments or their copies. I wanted to do the same. In Chile, my home country, it was impossible to study historical performance, but I met flutist Gisela Mornhinweg, who played the Baroque flute well and was well-versed in these matters. She told me the steps to follow. Shortly after, I got a Baroque flute, not very good, but it served a purpose, and I started studying. Later, I went to the Netherlands, where I began my career as a historical flutist.

Q: What are the main differences between the historical flute and the modern flute, and how do these differences affect your interpretative approach?

The transverse flute, from its beginnings, underwent rapid evolution according to the needs of performers and composers writing music for it. Initially, it might have been a piece of bone with a hole to produce sound through the mouth and a few holes to change pitch with the fingers. From bones, they transitioned to bamboo, using the same technique, a hole for the mouth and others for the fingers. Then, as metal tools improved, flutes began to be made of wood, and this was the material used until around the mid-19th century when metal began to be used to build flutes. While some study and research flutes from periods before the Renaissance, the term “historical flute” typically encompasses instruments from the Renaissance to around 1850 when Theobald Boehm built the first metal flute. The common or simple flute was made of wood in the Renaissance, with a mouthpiece and 6 holes, tuned to D, limited to being a diatonic instrument. In the Baroque era, a key was added to play other notes, and more keys were gradually added, making interpretation more challenging but improving sound quality. However, the flute remained a diatonic instrument. Boehm came up with the idea of having twelve holes in the flute, one for each note, and invented a new key system. The flute had become a chromatic instrument, able to play in any key effortlessly. That’s the significant difference between historical flutes and the modern flute.

Understanding this challenge significantly affects musical interpretation. For example, playing in D major is quite accessible on the Baroque flute, but playing in C minor becomes a serious problem. J.S. Bach knew this well when composing the Trio Sonata from the Musical Offering, dedicated to King Frederick.

Q: What is your opinion on the importance of historically informed performance in early music, and how do you apply it in your work?

For me, historically informed performance in early music is akin to archaeology. We need to investigate through sources, writings, anecdotes, chronicles, and also through the original instruments that have been found. This helps us recreate a sonic result, which may change as new technologies aid research. This is crucial for preserving universal musical heritage. However, I believe that the artistic value of the music is very important, motivating me to transmit it to new generations.

Q: Who are your main influences and references in the world of historical flute and early music in general?

One of the performers who significantly influenced my life as a musician was Wilbert Hazelzet. A simple CD of C.P.E. Bach’s music that I bought changed my perception of the flute and music in general. It was an inspiring moment. Eventually, Wilbert became my teacher, and with him, I learned to discover this fascinating instrument.

Q: What specific aspects of the historical flute and early music are you most passionate about, driving your continuous artistic development?

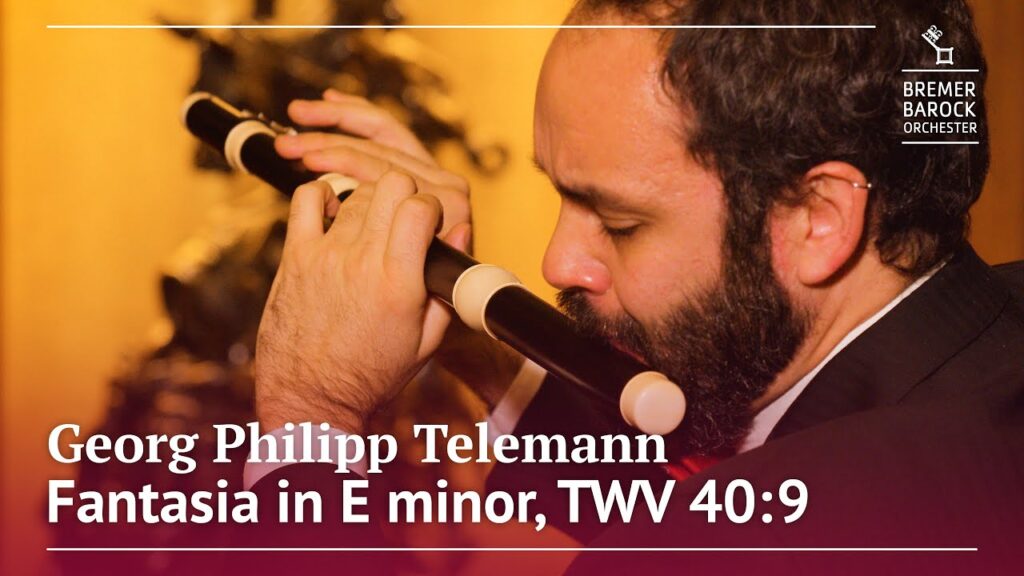

The sound, the blend of rustic and refined qualities in a wooden flute. Also, its ability to evoke various moods, from the contemplation of sadness in an adagio (2nd movement of J.M. Leclair’s Concerto for Flute in D major) to the euphoria of an allegro (4th movement of G.P. Telemann’s Concerto for Recorder and Transverse Flute in E minor).

Q: Can you share any noteworthy experiences, amusing anecdotes, or particular challenges you’ve faced in your career as a historical flutist?

I believe that in a musician’s life, each experience is noteworthy. There is always something that remains as valuable learning, be it a success or even a challenging experience. One such experience for me was participating in the “European Academy of Ambronay,” directed by Sigiswald Kuijken that year. He taught us a lot about style and precise aspects of Baroque music interpretation; we were working on J.S. Bach’s Mass in B minor. However, he also taught us the importance of listening to each other and working as a team.

Q: Can you tell us about any notable projects or collaborations you’ve been involved in as a historical flutist?

One project I found very interesting was recording the CD “Bach to the Roots” with the Baroque Orchestra of Bremen. This recording emphasizes an art that is rarely practiced, especially in Bach’s music: ornamentation. The CD provides a new and refreshing interpretation of standard Bach works, such as Suite No. 2 for Flute and Strings in B minor BWV 1067, where we give an original touch to the music, contributing with our own ornaments and improvisations.

Q: How have you experienced the evolution of networking and marketing in the field of early music throughout your career?

Initially, when there were no smartphones (I’m not that old, but I belong to the generation before these), the only way to promote your music was through concerts and contacts, and if you had the means, by recording albums. Nowadays, with new technologies, it’s much easier—you upload music to a streaming platform or a social network, and your music can cross oceans. This has many advantages but also disadvantages, as live music loses its value. Live concerts have increasingly fewer audiences, which is a serious issue. As the renowned conductor Sergiu Celibidache said, microphones cannot capture the “transcendental experience” that occurs between musicians and audiences; this remains in the intimacy of the concert hall.

Q: How do you manage your online presence to stand out in a market where authenticity and history are so important?

That’s a good point—authenticity. Generally, when I upload a video to my Instagram account, I try to keep it as unaltered as possible to preserve authenticity. Of course, I apply a few cinematic filters to hide facial imperfections.

But joking aside, I believe that for artists in general, a fairly active online presence is crucial, especially for multifaceted artists. This allows them to showcase their different facets. In my case, it’s very useful because, besides being a historical flutist, I’m also a composer. So, my Spotify or YouTube channels are crucial for my development.

Q: What is your perspective on teaching historical flute, and how do you share your knowledge with younger generations?

Teaching is the final step to retaining something learned, creating a cycle. While I don’t formally teach historical flute at a university, I have several students to whom I pass on what I’ve learned. This is beneficial not only for my students but also for me, as it helps me reflect and consider different perspectives on things I took for granted. Teaching is truly enriching.

Q: Do you have any advice for musicians considering delving into the interpretation of ancient music and historical flute? What advice would you give to your first-year conservatory self from your current perspective?

Many old-school teachers used to say you should focus on playing only one instrument. Myths like “if you play the Baroque flute, you’ll lose your embouchure on the modern flute” or “you can’t play both oboe and flute” existed. My opinion is that you should try everything; it opens up countless possibilities. It’s like a person who speaks many languages; they can communicate with more people. There’s nothing wrong with playing the Baroque flute and the modern flute, or the Baroque flute and the recorder, or the oboe and the bassoon. If you can play both, you can explore much more music.

One piece of advice I would give to my first-year conservatory self, aside from spending hours alone with my instrument, is to consume more art. Read more, listen to a variety of music, experience it live, go to the cinema, watch dance performances, and visit art museums. All of these activities develop appreciation, creativity, and a personalized taste.